When I was at Guild, we would think creatively about “skin in the game” as an incentive for how we could encourage better student outcomes. We expanded the concept beyond just money, which is how it is traditionally conceived, but also to include time and effort.

There is quite a lot of research that backs up the idea that when learners have skin in the game, they have higher graduation rates.

But this begs the question around why students with student loans are dropping out and defaulting?

There are many reasons why, but two of the main ones are:

The socioeconomic composition of college debt holders (Black learners typically assume $25K more in loans than their White counterparts1 and first generation college students accrue more debt than their counterparts2). The onerous interest rates and high amount make it really difficult for lower income households.

Perverse incentives for colleges and universities to address debt. 15% of Federal Stafford Loans, for example, go to students at for-profits, even though they only account for about 5% of the student population. Students at for-profits take on more debt and default at higher rates. And even private non-profits are all-in on increasing tuition without any meaningful increase in student services.

Colleges should be on the hook for student loans

What if we applied the concept of skin to game, not to students, but to the bag holders. If colleges and universities had to risk share, then maybe they wouldn’t be so predatory–and maybe they wouldn’t be so quick to raise tuitions, which have quadrupled over the past fifty years, even when accounting for inflation (from about $8K to $33K), and whose compound annual growth rate is more than double the consumer price index (6.7% since the 80s, vs. 2.9% for CPI).

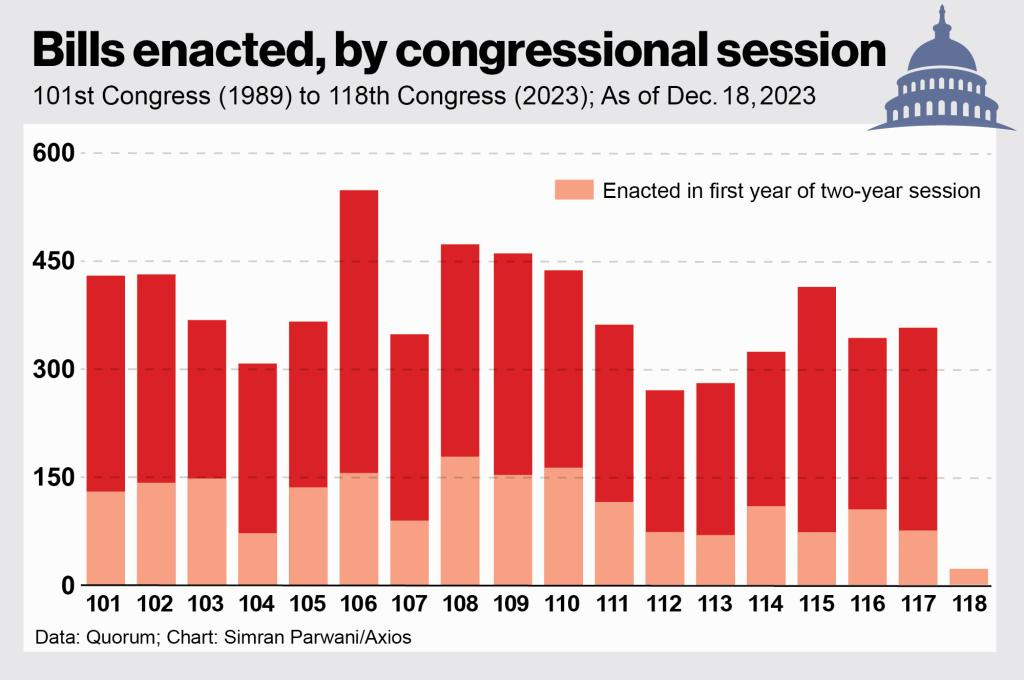

This risk sharing is a pretty radical idea, and one that has made its way into the GOP-sponsored College Cost Reduction Act. The bill is a mammoth one (a whopping 224 pages), with almost no hopes of passing due to some of the provisions included, such as limiting the amount of money students can borrow for college to $50K (but also the general congressional dysfunction). But one of its provisions is risk sharing, an idea that has merit and that should be considered:

Schools would be on the hook for student loans if their graduates made less than what was advertised, and more aid would be directed to institutions with higher outcomes and lower tuition.

What would happen if colleges had to repay loans?

Specifically, the bill would require programs to calculate an earnings price ratio (EPR) for each degree and certificate.

“For instance, graduates of the psychology program at the University of Southern California earn a median salary of $49,000 shortly after graduation, while their total tuition liability for four years is $156,000. The EPR for this program is equal to $49,000 minus 150 percent of the federal poverty line, divided by $156,000; the quotient is a value of 0.18.

…a program with an EPR of 0.18 triggers a liability equal to 82 percent of balances in nonpayment. Schools can therefore reduce their potential risk-sharing liabilities by reducing tuition, which will raise their EPR. Schools with high EPRs may also be eligible for a PROMISE Grant.”

The Pros:

Colleges and universities would be more aligned to student interests, aka graduating and optimizing earnings. They would be more transparent and honest about the lifetime earnings potentials of their programs. Schools and programs with high EPRs would get more funding. Anytime stakeholder alignment happens like this (taxpayers, institutions, learners) that has the opportunity to be genuinely good for society.

Many graduate programs would be forced to lower their tuition, since, in the absence of increasing earnings potentials for their learners, that’s the only EPR lever they have. About 41% of graduate programs don’t justify their costs: That is, their graduates don’t increase their lifetime earnings enough relative to the opportunity cost of the program.

The Cons:

While the effects should be studied more (many critics worry that it would impact community colleges or colleges with more diverse student bodies), the spirit of it is interesting. It could, however, lead to colleges lowering their “risk tolerance” by accepting fewer students from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds or certain protected classes.

Some programs would be shuttered entirely, especially graduate programs with negligible impacts on earnings, such as Education and Social Work, or some liberal arts majors. This is sad for society, but also forces us to reckon with issues that are broken about society: The fact that social workers have to do 1,200 hour field placements without compensation (see here for our past newsletter on this issue), or that teachers are horribly underpaid, etc. But it would, at least in the short term, likely ruin our supply of labor for select jobs and lead to an oversupply of high EPR degrees (which might then correct itself when companies have their pick of the litter?).

A recession could also impact this in wonky ways. It would likely lower the EPRs for every program (think the Great Recession or graduates during COVID).

But also, should I have become an English major? Probably not, but it does mean this substack is lit…erature?

Either way, it’s interesting that both parties are now contemplating really radical approaches to tackling student debt. It’s kind of heartening, even if there’s only a non-zero chance of a higher education reform bill passing.

Note: We’ll be taking a brief break over the next two weeks. I’m going on vacation, but we’re also interviewing operators and employees at some major EdTech companies to deep dive on certain topics (Guild, 2U, etc.), which we’ll be releasing (some to all of our subscribers, some to just our paid ones).

Source: Data Education Initiative

Source: Pew Research