Why We Need to Prioritize Mental Health Support for Educators

20% of teachers with 10-19 years of experience are leaving the profession. What can we do to help?

Updates in the Market

BYJU promised it would deliver its FY22 financials by September ‘23. That window is closed and their financials are still MIA. Add this to the list of bad news piling onto BYJU

A disability royal commission in Australia was split on the issue of whether to segregate neurodiverse learners from mainstream education. Over the past decade, Australia had built an additional 106 special education schools (to 520 total). Studies show that students with disabilities have better life outcomes when “mainstreamed.” (Source: The Guardian)

Federal student loan payments are set to start on October 1. On Friday, the Education Department set out a plan to provide debt cancellations for some subset of borrowers (such as those whose balances are now greater than the initial loan balance)

Cartwheel raised a $20M Series A last week. They provide tele-health services to schools

Cartwheel’s finding raise is a nice segue into this week’s subject: The mental health crises impacting teachers and students.

It’s impossible for us to make academic progress without addressing the mental health crisis impacting educators and students. Teachers churn, disciplinary actions soar (including—as we’ve mentioned in the past—school arrests), and students don’t have the social and emotional wellbeing to succeed.

We're losing young teachers AND our most experienced educators.

Pre-pandemic, 75% of teachers planned on staying in the classroom until retirement. It's now about 69%. For teachers with 10-19 years of experience, 20% left the workforce since the pandemic. It’s particularly bad to churn experienced teachers in the US, because 50% of ALL teachers leave the classroom within the first 5 years.

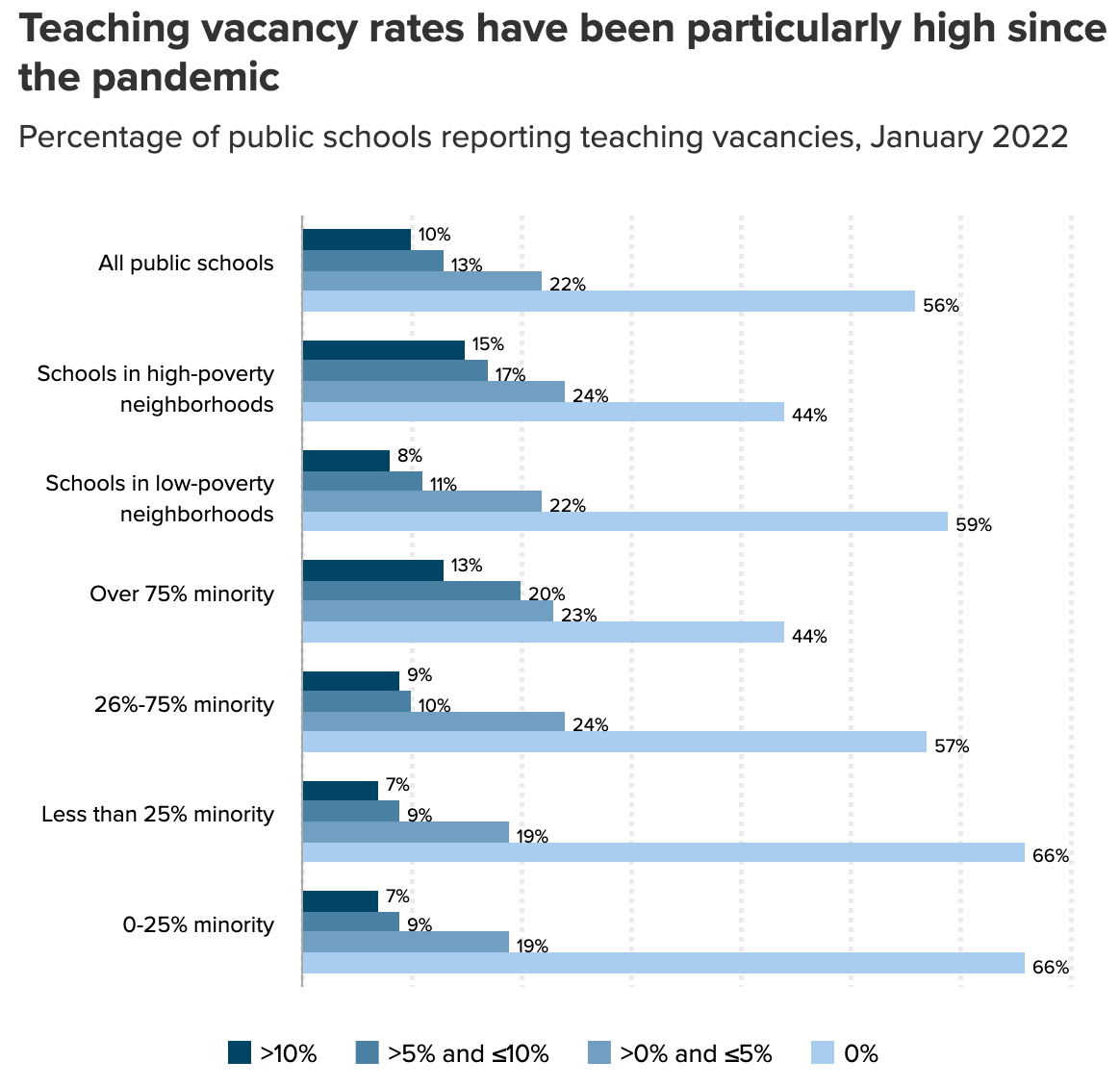

These shortages are especially acute for SPED and STEM, and particularly in high-need schools.

Source: Economic Policy Institute

The two largest contributors to teacher turnover are low compensation and stress. Low compensation is straightforward. We need to pay teachers more. Adjusted for inflation, teacher salaries have declined over the past decade (Source: NEA).

We could probably spend all month talking about how we need to compensate teachers more, but instead we’ll look at the issue of stress and mental health.

75% of teachers report job-related stress, vs. 40% for working adults. Teachers also reported 2.7x higher rates of depression than their peers.

Yet teachers don't often receive counseling support from their schools and districts.

But how do we tackle stress?

Making therapy accessible to teachers is one step…

In 2019, Georgetown University (through their Wellbeing in School Environments program) offered mental health treatment to teachers at a charter school in Ward 8. Half of the teachers enrolled in the first year.

Teacher turnover was reduced by 14%. 100% of the teachers who participated cited improved well-being and a positive impact on their students.

…resourcing mental health interventions for students is another.

We also need to provide more mental health resources and counseling to students--and especially students in high-need schools, where teacher vacancies and turnover are highest. In NYC, about 25% of schools lack a single social worker, and of the ~75% that do have social workers (about 1,100 schools), 80% failed to meet the recommended ratio of 250 students : 1 social worker.

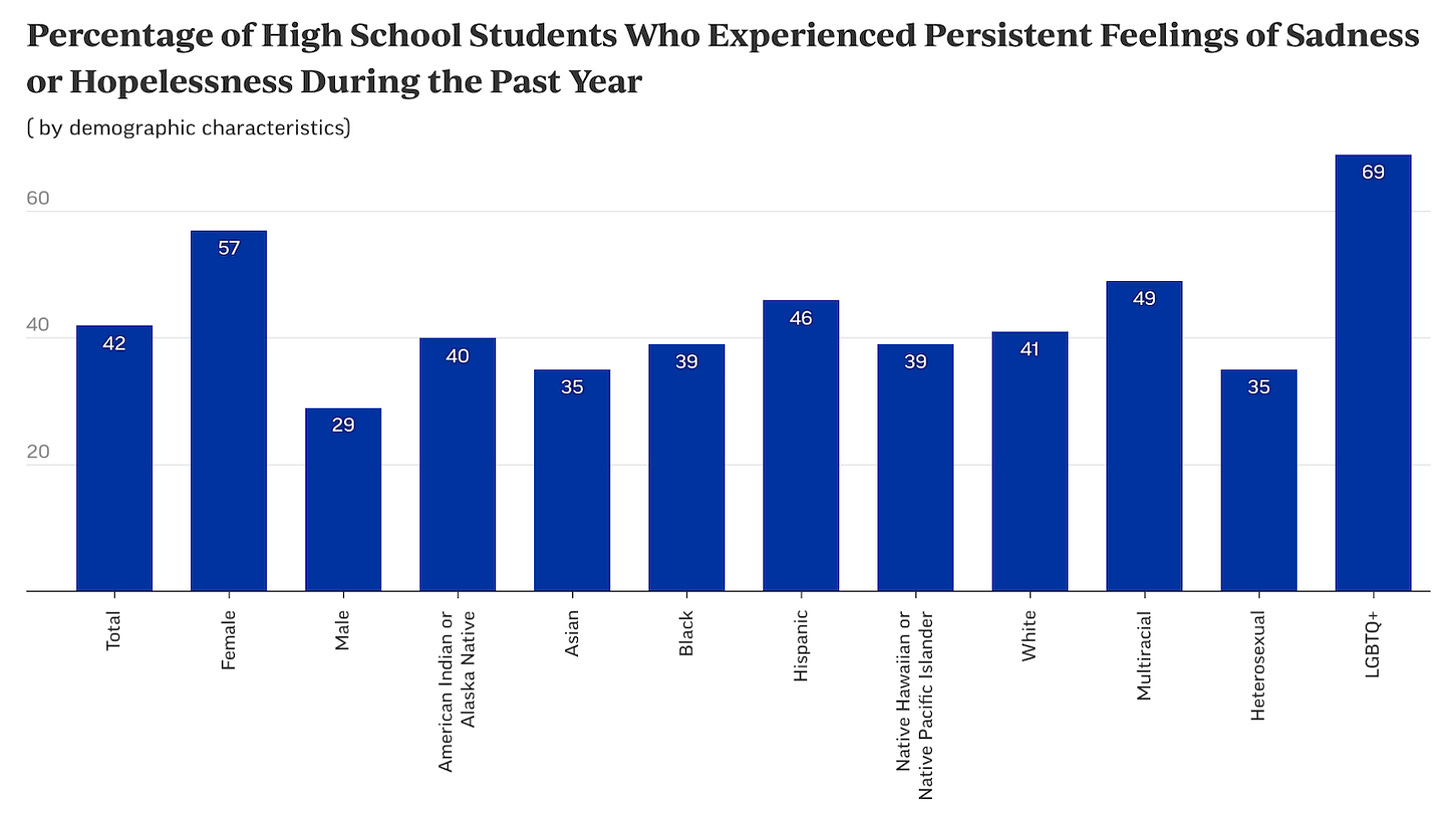

3 in 5 girls report feeling persistently “sad or hopeless,” up 60% from 2011, according to the CDC.

Some school districts do provide therapy for their educators. Newark Public Schools (NPS) offers up to 5 paid therapy sessions through a provider I’ve never heard of, in a brochure that’s hidden deep on their NPS site.

But these steps are constrained by supply-side issues.

A successful clinician or therapist can typically service a caseload of about ten or twelve students. Yet many schools have one licensed clinician for every 400 students, or none at all (the recommended ratio is 100 : 1). We need more therapists and mental health professionals in schools. It has massive knock-on effects: Michigan expanded their Resilient Schools Project through SRFs and has seen an improvement in test scores and reduction in violence.

In West Virginia, the Lincoln County Public Schools’ school board recently laid off 9 out of 10 of their social workers, despite protests from parents. There wasn’t any funding left after a grant expired, in spite of the fact that School Rescue Funds (SRF) don’t expire for another year. This was just poor fiscal management. They are possibly getting new sports facilities, though.

There are obvious funding issues. Declining public school enrollment is causing a funding death spiral for many large public school districts (see our past Substack exploring this issue here).

But the other issue is a lack of trained social workers. NYC has a shortage of counselors in spite of the DOE increasing earmarks. Projections show that nearly 40 states will see a massive shortage of social workers.

It is a high stress, low compensation job, and many social workers have to complete professional development on their own time and dollar. That’s on top of the crazy requirements to be an LCSW or MSW (1,200 hour unpaid field placements, paying for licensure, etc.) and the stress associated with it (about 70% of child welfare social workers have Secondary Traumatic Stress).

Median Annual Wages for Social Workers, 2016 (Source: BLS)

This shortage of social workers will be compounded by a perfect storm of: declining birth rates during the Great Recession, a looming college enrollment cliff (and an especially acute disinterest in social work degrees), and a inevitable retirement wave of Baby Boomer social workers. NYU Silver School of Social Work has reported fewer applications and declining enrollment (Shoutout: I would not know nearly as much about the dysfunctional state of social work if it weren’t for my partner, Michelle Rojas, and her organization, Corporate Social Work Collective).

To their credit, Congress passed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act in 2022 that has directed about $174M to Mental Health Service Professional (MHSP) programs to increase the pipeline of psychologists, counselors, social workers; and awarded about $140M to Local Educational Agencies and State Educational Agencies to help hire mental health professionals (although the funding only lasts 5 years).

What Lessons Can We Learn?

We are starting to get mental health right as an employee benefit. EAPs like Spring Health, BetterHelp, and Headspace help employees with easy access to mental health therapy and support. Headspace has more than 3 million users.

So what can we learn from employee benefits—or other industries, for that matter?

1. Scale Matters

This is the perennial issue for EAPs, and one that will be an issue for K-12 as well. If the average school in NYC has a 1:250 social worker ratio (and that’s perhaps being generous), then the issue is already scale. Compound that by cost-cutting measures at schools. Telehealth inherently solves this issue somewhat. It allows social workers to remotely support students in high cost of living cities.

To effectively solve the issue of scale, telehealth providers like Cartwheel will have to focus on contracts at the district-level or with large charter school networks. Schools can partner with each other to push for scale.

2. Building a Talent Pipeline

Are there other industries that have reversed a talent pipeline trend successfully? I’m not sure. It requires a somewhat coordinated response at multiple levels—or at least, high incentives. Usually, we compensate according to need. Long distance truck drivers, for instance. Logistics and shipping companies will pay for driving school, and people with a CDL A can expect to earn north of a $100K.

Unfortunately, the average salary for a school social worker in NY is $62K. Social workers could make more somewhere else. If we want more social workers, we need a multi-pronged approach:

Reduce the barriers to entry: A bachelor of social work needs ~400 hours of unpaid field work. To be a Licensed Master Social Worker in NYC (and in most places) you need an MSW (which costs tens of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of dollars), on top of an additional 900 hours of unpaid social work (and this used to be more than 1,000 until NYU Silver, etc., reduced it). The test alone costs $500. To be a Licensed Clinical Social Worker—to do therapy, etc.—requires another test, and an additional out-of-pocket 2,400 hours of clinical supervision. Holy f***. Just to make $60K? No wonder there is a pipeline challenge. We need to reduce the barriers to entry collectively. Schools of Social Work should partner with school districts to cover the test expenses and partial tuition of MSWs who plan on working in schools. Barring any incentive at the federal or state level, we need to reduce the field placement hours further. This is an industry wholly reliant on unpaid labor for highly demanding work.

Increase incentives / compensation: The Public Service Loan Forgiveness program discharges student loans after a decade of payments. Ten years is a long time to work in public service with few incentives aside from depreciating pay. We should allow qualifying public servants to access partial debt discharge earlier—at, say, 5 years, with a full discharge at 10. That allows some breathing room. For social workers specifically, all field work must be compensated. If a program requires unpaid work, then that program doesn’t actually function properly. Lastly, we need to pay social workers more—especially ones who work in schools. Easier said than done, but the federal government should earmark a sustainable, reoccurring budget specifically to support students’ mental health (vs. the expiration of a COVID-era budget). As the mental health crisis grows worse, we will pay for the social worker shortage in other, more expensive ways: Higher arrest and incarceration rates, higher absenteeism rates, lower academic results, lower lifetime earnings, higher rates of depression and addiction, etc.

3. Personal Relationships Matter

The students who most need mental health support are the ones who are also least engaged with school.

This is the same issue that’s plaguing remote tutoring (shameless plug for our other newsletter on this). There is no replacement for in-person tutoring or an on-site social worker. Teletherapy for students increases access for students and allows schools that might not normally have access to social workers (such as in the South or in poorer urban areas), but it’s harder for remote clinicians to build relationships with students—and it’s harder to make initial contact with the students who need that support, too (vs. an on-site social worker or counselor).

Students should receive consistent care from the same therapist or counselor, and receive regular check-ins. This will also, hopefully, help with chronic absenteeism.

What next?

I’m not optimistic. I think some startups, like Hazel Health and Cartwheel, will help make telehealth more accessible for schools and at-risk students. But these startups don’t address the talent pipeline risk.

While the Bipartisan Safer Communities act is commendable, the funding isn’t sustainable. The School-Based Mental Health Services grant program expires after 5 years. And then schools will probably follow in the footsteps of Lincoln County and fire the social workers hired through that grant funding.

Some Schools of Social Work are trying to adapt—although it’s too slowly. NYU Silver has reduced the number of field hours from 1,200 to the required 900 (which…isn’t actually much of an improvement).

I worry that the mental health crisis is staggeringly beyond our capabilities—especially with a possible government shutdown (even if delayed by a few months) and recession looming.

Oof. I need to talk to my therapist.

What do you want us to talk about in the future?

Michael and I have loved hearing your thoughts on different topics and your suggestions for new themes to explore.

From the Author, :

If you like our content, please subscribe to our newsletter. Michael (my co-founder over at Talent Lab) and I are both former teachers from Newark and Harlem and lifelong educators. We now work at two of the largest EdTech unicorns, and want to share what we’ve learned and know along the way. Your subscription means a lot!