In 2012 and 2016, the European Investment Bank invested £60M (that’s £120M total) into Swansea University’s Bay Campus and Singleton Park Campus. The Bay Campus, pictured below, is stunningly beautiful. It is also a weight on Swansea’s balance sheet. In 2024, the university had to renegotiate its lending terms to avoid default.

Swansea is emblematic of a UK spending spree on infrastructure. From 2014 and 2018, the UK spent £9.3 billion on university capital projects, like Swansea’s Bay Campus. This coincided with Theresa May’s 2017 decision to temporarily freeze university tuition at £9,250. That temporary freeze has persisted until 2025, when it will rise 3.1%.

The temporary freeze wasn’t a terrible decision. On average, British universities are the most expensive in the world, according to The Economist.

The problem is that these universities decided to increase their CapEx and OpEx so dramatically (non-academics make up half the university workforce) right when tuition and international enrollment were both capped.

Government regulators believe that 40% of universities in the UK are now running a deficit.

Bad time to be basic math formulas. On top of all of this is the weight on demand. Demographic cliff + reputational damage + commoditization are going to suppress demand further down the road.

Where have all the foreigners gone?

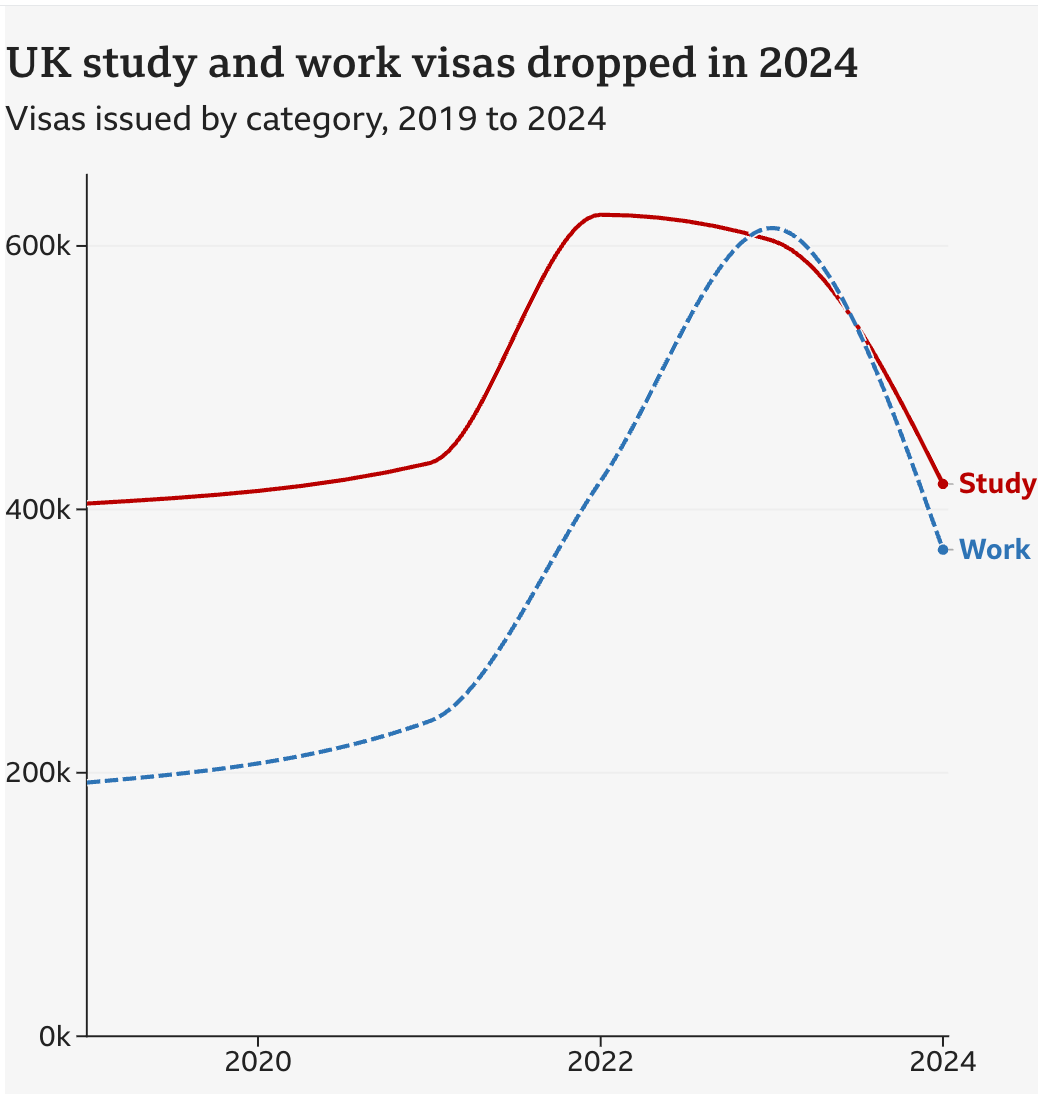

In the UK, visa restrictions and work-stay are both being cut. International students now have to leave 18 months after graduating, down from 24 months.

That’s slightly more welcoming than Canada, which is instituting caps on foreign students.

In the US, which mirrors the UK’s system, universities embarked on a similar spending spree. University of Oregon is running a $25.7M deficit. That’s a far fall from grace from 2018, when they broke ground on their $1B Knight Campus.

Like the UK and Canada, the US is closing its doors to international students, who pay full fare. NAFSA, the Association of International Educators, reports “limited to no visa review appointments for prospective international students in India, China, Nigeria, and Japan.” They predict a 30–40% decline in new international student enrollment. A July 17 report from Inside Higher Ed supports those dire proclamations: The State Department issued 22% fewer F-1 visas year-over-year, with a 15% decline for Chinese students. 78% of US universities are expecting a decline in foreign undergraduate and graduate students.

Policy uncertainty (like the legal back-and-forth between Harvard and Trump) are exacerbating the issue, with students opting not to take the risk and to study elsewhere. For example, India sends 331,000 students to US universities. Now that the US is debating a 50% tariff on India, it’s likely we’ll see some deceleration in attendance.

All your eggs in one basket

While the Trump Administration has exacerbated the pain that universities are feeling, fiscal mismanagement has long plagued higher ed. What kind of system are we building where spending is so egregious that a significant percentage of universities are running deficits (and as non-profits no less!)? Why are the very manifestations of our unquenchable search for knowledge building…lazy rivers? These places have PhD economists!

The problem is that universities (aside from those with big reputations, like Harvard) are in a commoditized market. You can get a degree online that probably has a better ROI than most in-person colleges. So now these universities have to resort to insane moves, like building a lazy river, or some campus overlooking the ocean, or a $1B research facility when everyone is trying to be a research institution.

Higher education is facing an existential crisis. High debt and worsening prospects are causing the public to question the value of a degree. Say what you will about AI, Trump, and demographics–the problems plaguing higher ed are largely of their own making.

So how do universities climb out of this hole? The answer isn’t great.

Many of them won’t. That’s tragic, but inevitable, especially in geographies that are already plenty-served, like The University of the Arts in Philadelphia. That’s not a nice answer, but demand is going to decline, and businesses ultimately close.

For areas underserved, especially in rural and/or low-income areas, we have the government step in for colleges or universities that specialize in high-demand roles or jobs that are aligned to regional demand.

I am 100% in favor of re-examining the tax-exempt status of universities that hoard wealth. My alma mater, NYU, is going to put me on a DNR list, but they have a real estate portfolio worth $15B. They are the wealthiest private landowner in the wealthiest city in the world. Harvard, meanwhile, has a $53B endowment. That’s larger than the GDP of 120 countries. Yale has a $41B endowment. Make ‘em pay!

All that to say, there really are no easy or palatable answers. Unfortunately, many colleges and universities will close this year. These universities are storied, and employ many people. Students will have their learning disrupted. The shame, ultimately, rests with the administrators who walked, lemming-like, into the dustbin.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on the crisis in higher education in the comments. Especially in light of the tariffs and trade wars and impact on international students.

Did you miss our podcast?

Check it out wherever you can find a podcast, but here’s our Substack link to it! You’ll learn more about me and Michael: Our time in the classroom, with Guild and Multiverse, and more. Hopefully it contextualizes why we feel the way we feel–about things like educational inequity, the weird and wild nature of opportunity and access, and some skepticism about all the EdTech thrown at us.